pH and the Political Economy of Black Hair

Black hair treatments are a great example for thinking about how something like pH could matter for the intersections of innovation, politics, and commerce. Garrett Morgan, an African American inventor who patented some of the first versions of the traffic light and gas mask, accidentally discovered chemical hair straightening when researching an alkaline solution to clean sewing machines, and in 1913 started the Morgan Hair Refining Company. Madame C.J. Walker, who rose from poverty to become America's first female millionaire, developed her own scalp treatment formula. She was also an innovator in social justice; for example, her 1917 Hair Culturists Union of America convention became a rallying point for protests against lynch mobs. In 1957, Bernice Robinson, a beautician in Charleston, was selected by the NAACP to run an experimental adult education class that would raise literacy for voting registration. They reasoned that because she owned her own shop, there would be no danger of getting fired for her activism. These classes became known as Citizenship Schools, and were replicated throughout the Southern United States.

Many of today's black hair entrepreneurs have continued this tradition of combining innovation and social justice, often around the theme of seeking healthier treatments. In South Africa, Thokozile Mangwiro created the “Nyla” brand of hair treatments and baby oils using an Indigenous tradition of Marula nut oil. In Detroit, Sheri Crawley began selling products with Tea Tree oil, an Indigenous tradition from Australia, and eventually created her own product line, Pretty Brown Girl, which encourages health and self-esteem for black youth. And Dora Marios in Tanzania, who provides a voice for low-income communities on her award-winning radio program, has successfully marketed a coconut baby oil.

One thing all the above have in common is that their ingredients are backed up by scientific research. Take, for example, Dora Marios' use of coconut oil on babies: several studies have shown it is effective for helping babies with low birth weight, skin inflammation and other problems, in some cases far better than mineral oil, which is the most common baby oil product:

But how do we know it is real research? Crazy claims are made for all sorts of ingredients, and it's easy to call something science just by using big words. Here are some clues:

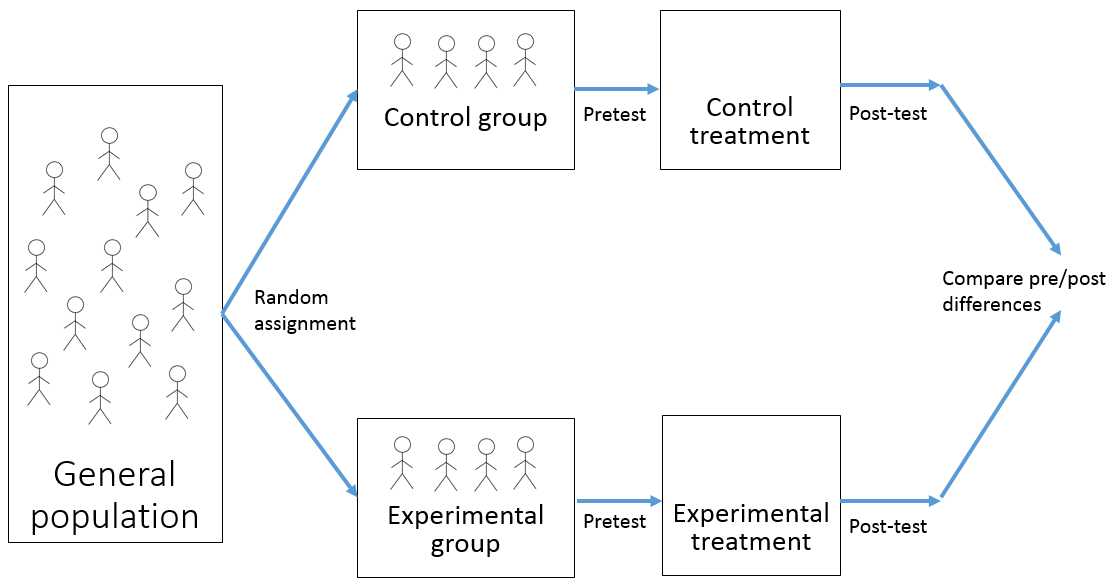

- Real research requires comparing the group with the experimental treatment (like coconut oil) to a similar group with ordinary treatment (such as mineral oil, the “control” group).

- Real research is published in real scientific journals. For example, we know “The Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies” is not science, because “meridians”—lines of magical power—don't actually exist. But if you look at the website it appears real. One way to tell is to find a journal's citation ranking. The higher the rank, the more scientists have cited it. For example if you look at http://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=2708&type=all you can see how all dermatology journals are ranked. The Journal of Cosmetic Science is #99 out of 139, so while not a top journal, it still counts as a significant scientific publication. And there we see another research experiment on coconut oil; in this case, showing it is better for reducing adult hair damage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12715094.

-

Real research does not use fake concepts:

“Detox” -- It is common to see advertisements for a “detox” food, pills, cream, etc. But no substance can remove toxins from your body; that is something only your liver, kidneys, and other organs can do. And while there are real ways to improve organ function, they are things like daily exercise, avoiding smoking and drinking, eating fresh vegetables -- not the stuff being marketed by “detox” scams.

“Cleanses your X” (where X is colon, liver, body, blood, etc.) -- see “detox”.

“Burns off the fat” -- L'Occitane, with 2000 boutiques in 90 countries, got caught advertising weight loss skin creams by the Federal Trade Commission. They have agreed to pay $450,000 to reimburse customers. There is no such thing as a weight loss cream.

“Cure-all” -- one of the red flags for pseudoscience is when you see claims for curing a long list of unrelated problems: “cures cystitis, epilepsy, PMS, ADD, autism, heart problems, migraine, psychosis, poor memory, arthritis....”

“The secret they don't want you to know” -- in the above example, we noted that scientific tests show that coconut oil outperforms mineral oil, a common commercial ingredient. So it is true that corporations will sometimes promote ingredients that are less helpful or even harmful (think of tobacco companies and cigarettes for example). But the science is not a secret. If it is real science, it is publicly available knowledge in established journals.